i wish one day i could put together a piece like this. it's a relevant piece. reviewing pop culture the way i see it, stating the obvious and genuinely ranting about it's current state of affairs. my emotions teetered throughout, excited by it's topic, bewildered by it's prose, angered certain tangents, only to be then brought back to the topic at hand, which is a review of food tv 2.0, a horrid state of affairs that the one sellout who kind of kept it real, mr bourdain, sold out to the max. (...i'm not as big of a bourdain fan as greenwald is. i would've run out of "no reservation" praise after one paragraph rather than the 2 he writes mid essay).

Eat Bray Love

The corruption of Anthony Bourdain, the return of Emeril Lagasse, and the state of food television

By Andy Greenwald on February 20, 2013

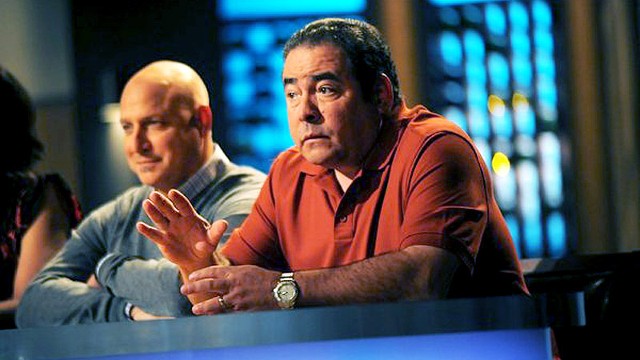

Adecade ago Emeril Lagasse was omnipresent, sprinkling catchphrases and cayenne nightly in front of a live studio audience. A lumbering, rump roast of a man who cooked like Paul Prudhomme but talked like the Gorton's Fisherman, Emeril was the unlikely poster boy of the transformation of what had once quaintly been known as "cooking shows" into a more unwieldy behemoth: "food TV." Fueled by the insatiable advertising needs of the Food Network and a viewing public suddenly interested in distinguishing deglazing from deveining, the staid format established by Julia Child and Jacques Pepin was chucked into the garbage like spoiled milk. It was no longer enough to stand behind a stove top and instruct. The new goal was to entertain. Chefs were required to prep themselves right alongside their mise en place, to garnish their dishes not with parsley but with personality.

And so, beginning in 1997, Emeril applied essence and kicked things up to varying notches. He employed a soft jazz band and cooked with Pat Benatar. He made garlic an applause line and convinced untold millions of Americans to try their hand at something called Urky Lurky. The goal remained ostensibly the same, despite the extra volume: to make home cooking appear doable and fun. But the extra noise soon began to drown out the message. Emeril endorsed toothpaste and floor mats and allowed someone to talk him into starring in an NBC sitcom.1 Eventually, the demands of celebrity scraped Emeril's plate clean, and by the time Emeril Live's goose was finally cooked2 in 2007, he'd unwittingly set the table for an entire generation of cheesy blasters still to come.

With no way to serve us an actual steak, the Food Network rebranded itself in desperate search of sizzle. The hyperactive appetite of television — for youth, for spark, for drama more genetically modified than a tomato in December — is far more demanding than any mere gastronome. And so the TV part of the equation began to outweigh the food. Legit cooks like Mario Batali and Michael Chiarello also went out the door. The rise of the hubris-devouring succubus that is The Next Food Network Star3 — and the long-term cheap replacement labor it provided — meant that their expertise was expendable, easily sacrificed on the altar of accessibility. Cooking isn't all that difficult, but cooking well absolutely is. And so the second generation of Food Network shows focused on making everything as easy as humanly possible, an interchangeable cavalcade of shortcuts and time-savers and "healthy alternatives," an endless slate of chipper idiots demonstrating idiotproof ways to successfully make sandwiches. The rest of the schedule was given over to a series of increasingly ludicrous competitions: The honorable Japanese Iron Chef begat a tarnished American version. Cupcake Battles escalated into Halloween Wars. Newer shows promised to reveal — and humiliate — the Worst Cooks in America. There's the even more execrable Rachael vs. Guy Celebrity Cook-Off,4 which revels in subhuman incompetence.

The schizophrenic network seemed committed to the idea of separating its viewership into either cartoony warriors or overmatched civilians, presenting the kitchen as either a battleground or a ticking time bomb. Food itself was either impossibly out of reach or beside the point, like fat floating on the surface of a broken sauce.

Fermenting just beneath Emeril's rise, the sourdough to his bubbly yeast, was Anthony Bourdain. The acerbic former junkie turned professional raconteur talked more smack than he'd ever injected, particularly on the subject of chefs on TV. (Emeril, for example, was both an "Ewok" and a hack.5) Bourdain was a proud and snarly outsider, a thoroughly undistinguished line cook lifer suddenly handed a bullhorn on the back of a surprise bestseller. The chip on his shoulder was the size of a Yukon Gold. But, first on the Food Network and then on the Travel Channel, Bourdain proved himself to be a peerless ambassador for the extremes of cooking, high and low.

He was never half the chef Emeril was — something he'd be the first to admit — but he was twice as good on camera. No Reservations, which recently ended a triumphant nine-year run, was consistently one of the best things on television, a gorgeously shot valentine to global food culture. Bourdain's snark was always as much of an affectation as the earring and cigarettes — both now mercifully discarded — and so I never found him off-putting. Rather, I found him brilliantly and persuasively respectful, making the case that eating a raw seal eyeball or a bowl full of deep-fried crickets6 aren't isolated acts of gross-out machismo but a way to connect with people and traditions that existed long before Cool Ranch Doritos Locos Tacos — and will hopefully survive long after that abomination is wiped from the earth.

At its foul-mouthed best, Tony Bourdain's shtick is absolutely empowering, but not in thefaux-populist manner of a Sandra Lee or Guy Fieri. What's made his voice so important is his steadfast refusal to coddle anything but eggs.7 Unlike most food shows, the central message of No Reservations was actually, no, you can't do this; you can't cook it, you can't re-create it, you can't dumb it down. Bourdain was a knight-errant of good taste, a champion of expertise and authenticity. Real food experiences, he argued, whether at a sushi counter in Tokyo or a hot dog stand in Chicago, are worth seeking out. Appreciation is just as important as enthusiasm.

Which is precisely what makes his involvement in ABC's The Taste8 so disheartening. "This is a cooking competition unlike any other," Bourdain brayed at the start of the series last month. It was a lie. There have been plenty of terrible cooking competitions in the past, though maybe none as teeth-grindingly cringey as this one. Conceived as a glitzy, kitchen-oriented version of The Voice, here it's the judges who must repeatedly open their gobs, the better to shove in an unending conveyor belt of porcelain spoons. Every spoon arrives laden with a "perfect bite," each one cynically crafted by one of a well-groomed armada of knife-wielding fameballs. The idea, the show repeatedly tells us with all the subtlety of a Sriracha shooter, is that only through blind tastings and novelty flatwear can food actually be judged by its most important characteristic: The Tas — oh, I can't even bring myself to type it.

Look, it's perfectly fine for Bourdain to cash in and try new things. He's spent a decade traversing the world, consuming calories as if they were frequent flyer miles, and collecting hangovers like snow globes. He's 56 years old, married, with a 5-year-old daughter. Everyone deserves a chance to experiment, and I've got nothing at all against selling out.9But Bourdain's entire post–Kitchen Confidential career — embodying his bedrock belief that food cannot and should not be separated from the richness of experience that surrounds it — has been an eloquently stated and vibrantly lived refutation of everythingThe Taste stands for. Now he sits on a garishly lit soundstage, defanged like an aging circus lion, ginning up halfway constructive things to say to deluded Capoeira instructors who make "food for awesomeness" when the only reasonable response would be laughter.

Slumming alongside Bourdain as judges/mentors are Ludo Lefebvre, an actually gifted French chef who operates a wildly popular pop-up restaurant in Los Angeles,10 Nigella Lawson, the endlessly charming doyenne of British domestica, and onetime Top Chef loser Brian Malarkey. OK, maybe only 75 percent of the panel is slumming: The impossibly plastic Malarkey is the most aptly named reality-TV personality in ages, a self-proclaimed fish cook whose actual specialty is ham. Bourdain's Rolodex is put to good use, too, as a dazzling assortment of legitimate geniuses, from Gabrielle Hamilton to David Kinch, parade shell-shocked through the sea of overmatched, yoga-bowing amateurs. But not even this can save the show from its central conceit. A blind taste test may be "pure," but it also makes for dull television, as the judges chew speculatively and toss out the occasional inaccurate noun ("Is that watermelon? And some kind of fruit?" "Lamb. I think it's lamb"). The rest of the hour is filled with the backstories and histrionics of the wildly uninteresting finalists, who range from moderately talented professional cooks to moderately talented home cooks. By trading on (false) Bourdain-ian orthodoxy,11 The Taste has actually robbed itself of the unhealthy but delicious artificial flavoring that powers most reality-TV shows: personality. It's a bland, underseasoned mess.

The main takeaway here is that amateurism just isn't all that interesting. There's an ugly, undeniable thrill to watching puffed-up losers flame out in the audition rounds of singing shows — how dare they not know how bad they are! — that's simply absent in food competitions. At worst, these clumsy home cooks are still struggling to prepare hot food for their families. A bland Chilean sea bass contributes more to society than a butchered Edwin McCain song. Cooking at a high level demands real ability and even realer dedication. A vocal savant could feasibly go from the American Idol stage to Radio City; the best contestant on The Taste would struggle to last five minutes in the kitchen of the restaurant on the corner of my street.12 I watch food shows for competence and excellence, and for the same reason I disdain college sports: I like seeing the best.

Thankfully, there remain two cooking competitions mostly untouched by the ravages of reality TV. The first, rather surprisingly, is not only on the Food Network, it's become their signature series. Chopped is lean and unsentimental, a relentlessly rewatchable exercise in the sort of quick thinking and flexibility only possible in thoroughly Malcolm Gladwelled professionals. The contestants who do battle with baskets laden with fennel and fried egg candies — and each other — are culled from the swollen, mostly anonymous ranks of the people who actually cook our food. It's an entertaining mix of graying lifers and hungrystagiers looking for a way to pay off student loans, not fame. Not even Alex Guarnaschelli's affected death-stare can dampen the freewheeling vibe of loony inspiration. The recent Chopped: Champions' Tournament was the most entertaining television I've seen in 2013, marred only by the show's unavoidable original sin: It culminates in dessert. Forcing wildly creative savory chefs to break out the measuring cups and ratios in order to determine a winner strikes me as patently unfair, both to them and to us. It's like ending the Lincoln-Douglas debates with multiplication tables.

Still, even at its best, Chopped is what happens after boiling and reducing the sumptuous master sauce that is Top Chef. In its 10th season, Bravo's flagship remains a well-oiled, overly sponsored13 juggernaut. Despite the deplorable lack of trademark spoonery, it's here that the Bourdainian ideal is best expressed: skilled, overly tattooed tradesmen (and women) competing solely on the strength of their cooking. The occasional backstabbing or head shaving or Grand Theft: Pea Puree serve as side dishes,14 never mains. The best seasons by far — Las Vegas, All-Stars — have been the ones with the most talent, not the most fights. As with the NFL, parity here is a better idea in theory than in practice. The Texas season wasn't dulled by Paul Qui's dominant brilliance, it was saved by it.

The Seattle edition, which plods to its conclusion with the first of a two-part finale tonight, has been slowed by the creaks and groaners typical of an aging franchise; years of cherry-picking talent has resulted in a less dazzling cast, many with mouths bigger than their palates. And the addition of countless gimmicks to keep fan favorites in the game has been both confusing and exhausting.15 It helps, of course, that the judges — from Tom Colicchio, a Renaissance master of kindly bemusement, to Padma Lakshmi, that stoned and regal puma — remain rigorous and fair, as do the deep bench of prestigious guests willing to schlep from South Carolina to Alaska for the privilege of eating yet another "perfectly cooked" scallop. But mostly I remain a sucker for the marathon grind of the cooking and the hard-earned camaraderie it creates among the cheftestants; there's nothing better than the final episodes when the finalists share recipes, smokes, and thousand-yard stares; hardy survivors trapped in the same foxhole, cooking the same hens. Tonight I'm pulling for Brooke, the quietly confident cook from Los Angeles who's triumphed over unfried fried chicken and a crippling fear of both helicopters and cruise ships, to take the title over Sheldon, a genial hippie from Maui who, like all ukulele strummers, is constitutionally required to mention where he's from four times an hour.

But the real breakout star of Top Chef Seattle isn't even in the competition. It's Emeril Lagasse. Now in his second season as an adjacent judge, the onetime garlic tosser is heavier and slower, a Wookiee in winter. Stripped of his catchphrases and his band, Emeril has revealed himself to be kind, patient and insightful, able to articulate the nuances of food we'll never taste with expert, understated flair. The best moment of the season came last week, when he cooked a meal alongside Roy Choi, hipster godhead and the man responsible, for good or ill, for the "food truck revolution" that already feels as dated as sun-dried tomatoes. Over plates of braised shortrib and cornbread, Choi explained how seeing an episode of Emeril Live at his lowest point transformed him from a "scumbag" into an acclaimed chef. "I was really in a bad place and this dude was on the TV, man," he said, fighting tears. "Emeril popped out the TV and just slapped me across the face."

The story kicked everything up to a notch not even Emeril was prepared for. ("Wow," he said, simply. "That's really cool.") But it made for riveting viewing just the same. It was food and it was television, satisfying, sharp, and sweet.

0 comments:

Post a Comment